Sometimes, there's just not enough sunshine.

Just ask any indoor farmer. When the sun hides too much, they have to switch on the greenhouse lights to nourish the crops. It works, but it’s costly: Electricity can fry profit margins.

A pair of researchers at the University of Georgia came up with a novel idea. What if indoor lighting could be calibrated more precisely to account for changing weather and the differing daylight needs of crops?

Erico Mattos and Marc van Iersel figured out how to do just that. They launched Candidus, a company that develops technology and “lighting strategies” to optimize light for indoor farmers, saving them money and increasing their crop yields.

Like so many university explorers, Mattos and van Iersel had deep technical expertise and more than a little ingenuity. Van Iersel has published more than 120 scientific papers and addressed audiences all over the world; Mattos devised new forms of indoor LED lighting. But they lacked experience starting and running a company.

So they did what more and more UGA faculty and students are doing these days. They enlisted the help of Innovation Gateway, the university’s entrepreneurship enterprise that turns good ideas and inventions into marketable products and promising companies.

With seed funding from GRA’s venture development program and seasoned advice from Innovation Gateway, Candidus is now moving headlong into product development. It’s one of 120 budding and burgeoning UGA endeavors in the Gateway, each doing the hard work needed to get a fair shot at success.

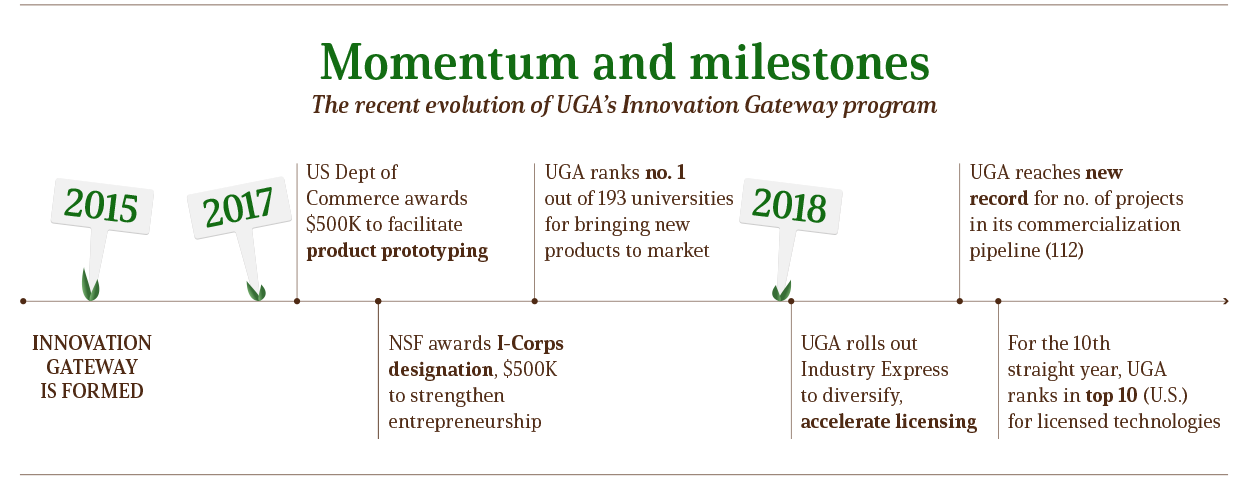

That number is just about unthinkable, given Innovation Gateway’s youth. The program was formed in 2015 when the university blended its tech transfer office with the Georgia BioBusiness Center, an incubator and accelerator operation.

“At the time, we had about 20 resident projects, most of them formed companies that were looking after themselves,” says Ian Biggs, COO of the Gateway. “Another 10 projects needed more hands-on help. The vast majority of these companies were in the life sciences, and those kinds of startups take a very long time to grow.”

Forming new ventures sounds easy enough, but at a university with a limited startup culture, it required re-inventing how to encourage and help researchers succeed as entrepreneurs.

It helped that UGA had a relatively new and deep pool of potentially marketable technologies in its College of Engineering, which formally opened in 2012. The college now enrolls 2,300 students, a number that can signify critical mass for R&D. More students means more hands-on exploration, research dollars and research faculty.

While the numbers back then are somewhat low for an institution the size of UGA, the university was no stranger to product innovation. For 10 years running, UGA has ranked in the top 10 nationwide for licensing its invented technologies. For even longer, it has ranked in the top 20 in revenue from licensing. Much of this success sprung from an innovation portfolio in horticulture and agriculture: UGA has done pioneering genetic work in hydrangeas and blueberries, turf grass and livestock. “Virtually all of the peanuts grown in America come from UGA genetic engineering,” Biggs points out.

Even still, the university saw a real need to generate more start-up companies. “We want to see the impact of UGA research maximized,” says David Lee, the university’s VP for research. “And we want to ensure that discoveries made at UGA reach their full potential to benefit the public. The way to do that is to form new ventures as well as develop more industry partnerships.”

“Engineering has really helped grow our pipeline,” Biggs says, “but at the same time, entrepreneurship here is not all engineering and life science. When I look at our pipeline, I see we’ve got projects coming out of 15 different schools.” To punctuate the point, he notes that he was recently approached by an English professor on campus. “He had an idea for a product that could be commercialized. So we’re helping him, too.”

Filling the pipeline, Biggs says, began with reaching out across the Athens campus. He and colleagues visited deans to encourage them to watch for research projects that might have commercial potential. They showed up at faculty gatherings and at meetings for new licensing disclosures.

“Previously, if you had a patent, you were probably heading for the licensing group next,” he says. “We told them, You don’t have to make that decision right away. Come to Innovation Gateway, and we’ll help you work out the right pathway.”

Sometimes, that pathway takes a novel form, such as accommodating faculty who are reluctant to start a business.

“We’re running a kind of dating service between people who want to try entrepreneurship and those who have a good idea but no inclination to run a company,” Biggs says. “For example, we put together teams from engineering and the business school and gave them some technologies UGA has had for a while. We asked them to determine if they’ve got real market potential.”

“UGA has done a good job reducing the friction for faculty, postdocs and grad students to explore entrepreneurship,” observes Lee Herron, GRA’s VP for venture development. “They made the path much easier for those who might not have considered starting a company.”

Though the Gateway entrance is wide, a ticket of sorts is required. Company founders seeking help must meet seven criteria and submit documentation about market opportunity, potential competitors, financial projections and other baseline considerations.

Then, the real work begins. Biggs says for innovators to fairly evaluate their ideas, they should conduct dozens of interviews with potential customers in the marketplace.

“Half of startups fail because they produce something no one cares about,” he says. “It’s easy to fall in love with an idea, and it’s hard to let that idea go. The companies really have to work on their value proposition.” Sometimes, he says, startup founders discover a second idea that’s better suited for the marketplace than their original concept.

Two big developments in 2017 helped Innovation Gateway up its game in helping startups. The first was a $500,000 grant from the National Science Foundation to designate Innovation Gateway as an I-Corps site. The I-Corps program – which Biggs manages – accelerates NSF-funded research that the Foundation believes can readily benefit society. At UGA, the grant will fund five years of providing 30 entrepreneurial teams with mentoring, workspace, seed funding and other essentials.

A second $500,000 grant awarded that year – this one from the U.S. Department of Commerce – went toward improving prototyping for early-stage enterprises. Matched by UGA funds, it established a New Materials Innovation Center (NMIC) on campus, providing startups with equipment and technology to iterate product prototypes and test them on a larger scale.

“We have one team that came up with a bright idea for a medical device that holds a catheter in the right place during surgery,” Biggs says. “But they had to figure out, does it work? Can you clean it? Having a 3-D printed version of it through the NMIC was what they needed to get started.”

When asked to name a few projects inside Innovation Gateway that have impressed him, Biggs doesn’t hesitate. One is a gel that slow-releases a vaccine, potentially prolonging immunity. Another is a new encapsulation technology that delivers medicine more precisely inside the body. There’s also a catheter forged with materials that prevent infection, lessening the number of times it has to be replaced.

Not all of the startups are in the first days of their existence. Biggs points to Abeome, a 15-year-old company developing monoclonal antibodies, as a more experienced company getting guidance from Innovation Gateway. “They’re once again on the move, and they have their own facilities now,” he notes.

“Ian does a good job tailoring services to companies based on their stage, whether they’re already developed or not yet formed,” GRA’s Herron says. “He’s got a good system of categorizing them and what they need at a particular stage. As a result, we’ve seen our deal flow with UGA increase over the past couple of years.”

The two entrepreneurs behind the precision lighting company Candidus agree. After being awarded a $5 million grant from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration in 2018 to advance their research, they’ve recently applied for a Phase 3 loan from GRA’s venture development program.

“Without Innovation Gateway, I’m not sure any of this would have happened,” co-founder Marc van Iersel said in a 2018 article published by the university. “All of this would have just been a really cool idea and a bunch of academic papers.”