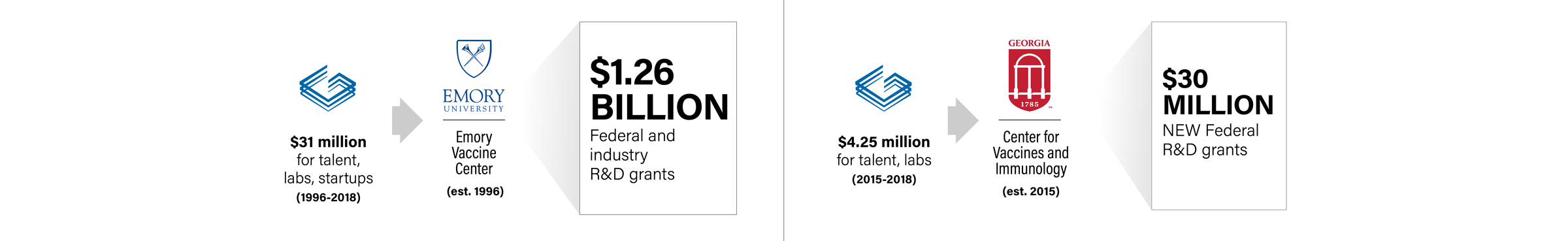

In Athens, UGA’s Center for Vaccines and Immunology (CVI) , led by GRA Eminent Scholar Ted Ross, has been a fast-rising star in basic and translational research since its founding in 2015.

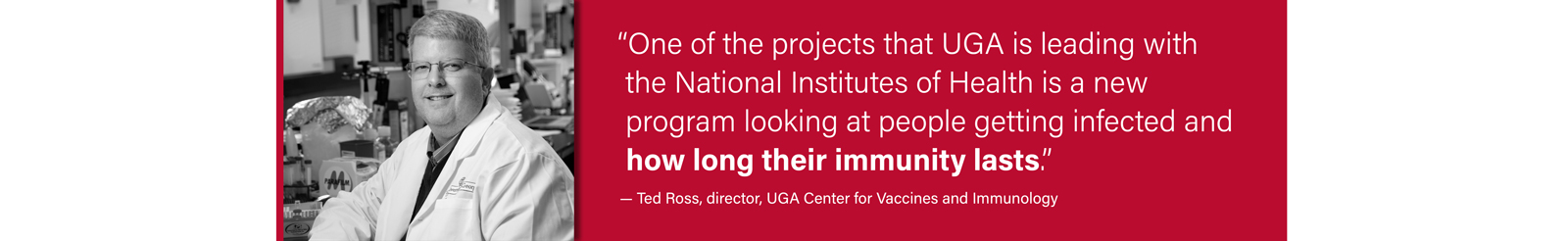

In October 2019, NIH announced it was awarding grants to the center to advance work on a universal flu vaccine – funding that could reach up to $130 million, making it the largest research award in UGA’s history.

An hour's drive to the south, in Atlanta, the Emory Vaccine Center (EVC) is regarded as the largest university-based vaccine research enterprise in the world.

Founded in 1996 by GRA Eminent Scholar Rafi Ahmed – who continues to serve as the center’s director – EVC has brought in more than $1.2 billion in research funding. The center also has an impressive portfolio of discoveries.

Ross and Ahmed joined GRA’s Board of Trustees meeting in September 2020 to discuss the COVID-19 pandemic and how their centers are fighting the disease. Here’s a synopsis of their remarks and answers to questions.

Rafi Ahmed: We sometimes forget why COVID is spreading so much. The answer is very simple: We’re all immunologically naive. Our bodies don’t have any pre-existing immunity. When that happens, that’s when we’re most susceptible.

Within a couple of months of the start of the pandemic, the Emory Vaccine Center identified antibody responses in COVID-19 patients. We discovered that infected patients quickly make neutralizing antibodies [to COVID-19]. And we also defined what target on the viral protein they were recognizing.

Based on that, they developed a sensitive and highly specific diagnostic test that would identify people making antibodies after COVID-19. It was very quickly picked up by Emory Hospital, and this test has now been widely used.

In terms of vaccine trials, Nadine Raphael, who heads our Hope Clinic, and other people have been involved in a very major way for the Moderna RNA vaccine trial. This has been one of the major activities of the vaccine center.

We are also very involved in therapeutic trials, with remdesivir and plasma therapies. The Emory Vaccine Center has been very involved in diagnostics, therapeutics, vaccine clinical trials – and interesting strategies to make a COVID-19 vaccine.

Ted Ross: It’s been a very intense six months for us at UGA. And I think we’re hitting the tip of the iceberg with what we’re doing with COVID in the next year or so.

Keep in mind that sometimes the first vaccines that are developed will be replaced with more effective vaccines as they come along in the next round. This is just the beginning of developing highly effective SARS-Cov-2 vaccines.

Our center is working with a lot of companies testing COVID-19 vaccines as well as vaccines developed at UGA. We’re looking at antibody responses as well as enhancing the T-cell responses against the virus. One of the things we’d like is to have not only a stand-alone COVID vaccine but also one that could be combined with the universal flu vaccine candidates that are being developed.

Q: Do you have any sense of when a vaccine might be approved and what’s the timetable for getting that to the people?

Ross: The initial approval is just the beginning of manufacturing and distribution. Because we’re immunologically naïve, it’s most likely going to take two vaccinations to get enough immunity. In the U.S. alone, you’d need 700 million doses to vaccinate everyone. And we’re not isolated, so we have to think about the entire world, too.

Ahmed: The rules of making a vaccine have been totally changed. We would never be thinking about the timetable that’s now being proposed. If you’re fortunate, it would be three to four years before a vaccine is developed, and is shown to be safe and effective.

Operation Warp Speed is a good program. For the first time in the history of vaccinations, the vaccines are produced before they’re licensed. That’s the biggest different in timelines. The federal government has given money to vaccine companies – a billion dollars or more. While clinical trials are going on, the vaccine is being produced.

Three Phase 3 trials have started. Others are right behind them. In the next three to six months, you are likely to get a signal that a vaccine is effective, and then a provisional license would be given very quickly. Let’s say in the best-case scenario, we get the signal by the end of the year. It’s not unreasonable that a vaccine would be available in the early part of 2021. But it all depends on whether we get an efficacy signal.

Q: Ted, you’ve said the flu vaccine can also be beneficial to those who get COVID-19 in terms of the symptoms. Also, everyone keeps talking about having to take this vaccination twice – does that mean the first time someone takes it, it does no good?

Ross: Since we’re concerned about both viruses co-circulating this winter, you could be infected with both in a six-month period. The flu shot will help with the flu symptoms, so if you get COVID, you at least won’t have the exacerbating effects of the flu to deal with. And from a public health point of view, reducing the number of people in the hospital and ICU will have a healthcare benefit.

As for just getting one of two shots, there still can be some protective effects if you only take one shot, but you won’t see the maximum protective effect until you get both vaccinations.

Ahmed: The fact that you end up with two immunizations is not that unusual. The HPV vaccine and the hepatitis B vaccines, for example, are also two immunizations. If you take the first but don’t take the second, it’s not totally useless. The second shot increases the magnitude of your immune response.

The three vaccines in Phase 3 trials all require two immunizations.

Valerie Montgomery Rice, president of the Morehouse School of Medicine and a GRA Trustee, then shared an update on her school’s involvement in COVID-19 clinical trials.

Rice: It’s so important to get people engaged from all backgrounds involved in clinical trials. Emory is one of the enrollment sites for testing the Moderna vaccine. And Morehouse School of Medicine (MSM) just got approved to be an enrollment site for the Novavax vaccine trials.

MSM was awarded $40 million this year from NIH. It’s to help ensure we have engagement from the community and create new educational materials that are linguistically appropriate for areas hardest hit by the virus. Raising awareness of the COVID-19 vaccine trials is a key deliverable.

MSM also got a $1 million NIH grant last week to combine community engagement efforts across schools. These are to communicate how to get involved in trials, therapies and vaccines, and to investigate testing capability.

Q: There are so many vaccine candidates in the pipeline. Are there front runners? Will we have combination vaccines? Will some in Phase 1 early trials shut down once others are approved?

Ahmed: In this race, the horse that crosses the line first may not be the best horse. We need a vaccine quickly. But there might be others that come out later. If you take one vaccine and take a second one that’s better later, that’s good.

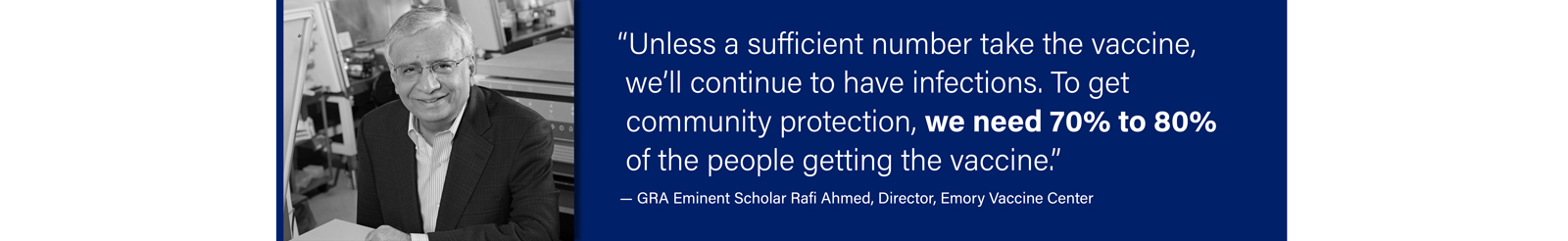

I don’t think anyone should wait for a better vaccine to come along. Unless a sufficient number take the vaccine, we’ll continue to have infections. To get community protection, we need 70% to 80% of the people getting the vaccine.

Ross: I think there will be multiple different vaccines that continue to come out and be developed. One area we can relate to in the vaccine world is influenza. There are still plenty of companies bringing vaccine candidates forward. There are always ways to improve the effectiveness and economics of the vaccine. I suspect the COVID vaccine will have many different companies with different products.

Q: Patients present with a wide range of symptoms. Will there be a range of vaccines that are targeted? Or will one vaccine work for every patient?

Ahmed: There’s great variability in the disease spectrum. Some get a very mild version, others much more severe. But I don’t think we’ll be thinking about one for those less susceptible versus more susceptible.

Q: Please comment on point-of-care antigen tests with results in minutes – there are all sorts out there, but it doesn’t’ seem that any of them are at the point where you could allow people to go to something like a sporting event?

Ross: Having a rapid test would be nice, but we’re not there yet. We’re still dealing with a lot of the basic information about what’s considered a positive result on antibody. We have a lot of work to do.

Ahmed: There are major efforts going on for rapid diagnostic tests. That would really help. But the challenge is the more rapid you make it, you lose out on sensitivity – and even more so, on specificity. These two have to be in the right formulation with ease of use.