If you’ve ever gotten help from a digital assistant – through your phone, or maybe that little speaker in your kitchen – you can thank GRA Eminent Scholar Larry Heck. For decades, he’s been at the epicenter of developing the artificial intelligence behind these and other technologies.

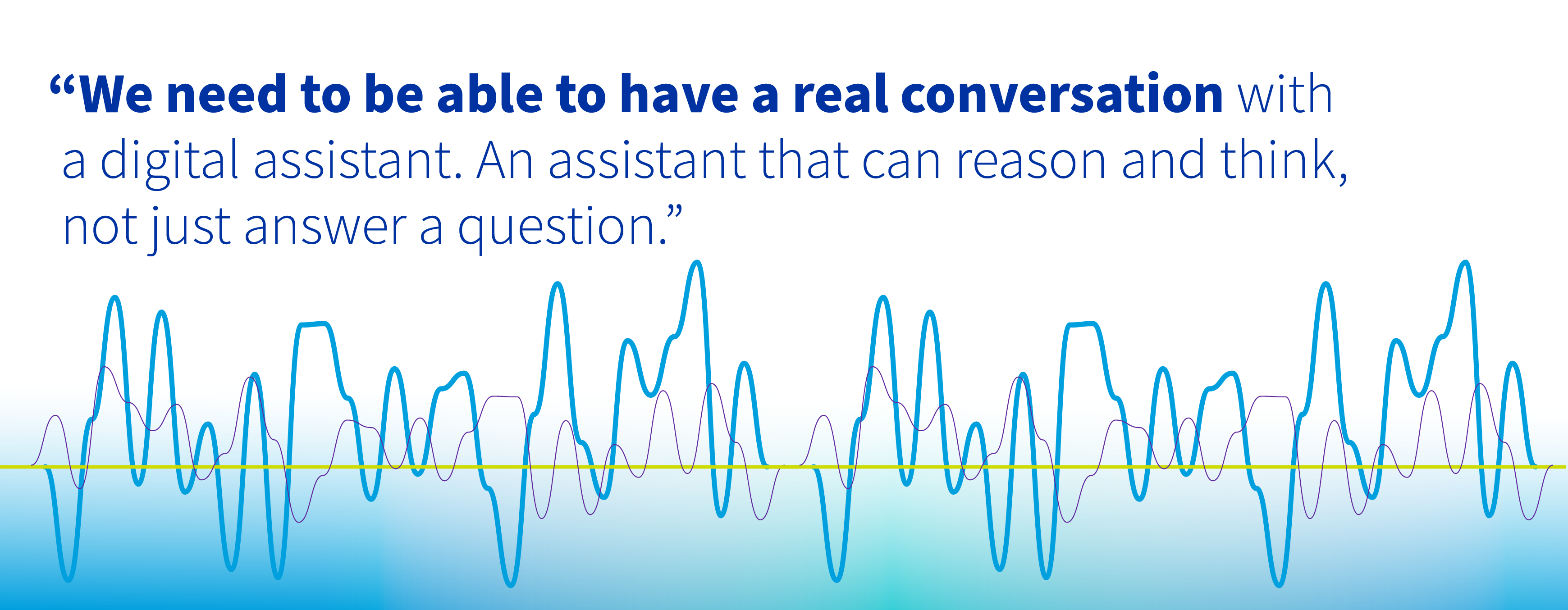

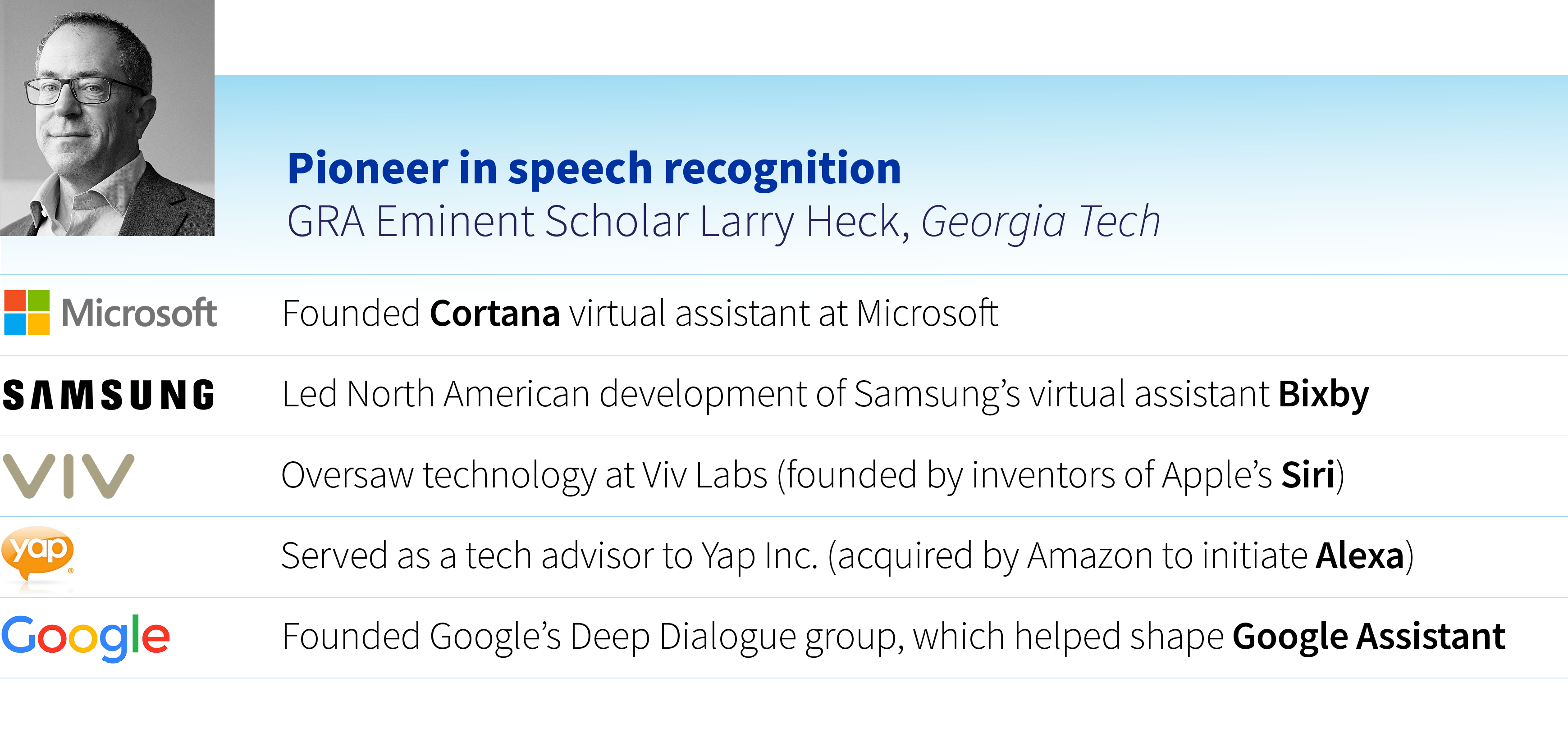

Heck founded the Cortana virtual assistant at Microsoft, and he led North American development of Samsung’s Bixby.

He oversaw technology at Viv Labs, which was founded by the inventors of Apple’s Siri, and served as a technical advisor to Yap Inc. — which Amazon acquired to initiate Alexa.

And he founded Google’s Deep Dialogue group, a longer-term research effort supporting Google Assistant.

In 2021, GRA helped recruit Heck to Georgia Tech, where years ago he earned a master’s and Ph.D. His arrival was a major addition to elevating Georgia’s profile in developing artificial intelligence for a variety of uses. Here, he shares his thoughts on where AI is heading – and what it will take to get there.

How did we come to have the digital assistants we have today, like Siri, Alexa and Bixby?

It was actually a long slog of incremental work in all of the components. I remember having dinner back in 2010 with Adam Cheyer, one of the founders of Siri. I had worked on a project with Adam at the Stanford Research Institute (SRI) in the mid 90s to create an SRI office assistant.

At that time, nothing seemed to work. Most of the component technologies, like speech recognition, were still lacking in some respect or another. In our 2010 dinner, we were discussing why virtual assistants finally starting to work. We concluded there wasn’t one particular breakthrough or silver bullet. More like a culmination of many things.

Like what?

Well, like web search using machine learning algorithms, which provided a very large-scale language model. And the emergence of the app ecosystem, particularly with Apple. Those two were kind of the trigger. The iPhone capitalized on this evolving infrastructure and made full Internet search mobile. And along the way, voice search, voice-driven apps. It’s really a long and quite complex story.

You have a story about introducing your dad to voice-activated technology years ago.

I had him call an airline and interact with their voice-activated system. It failed miserably for him. He said the phone system was way better back in the 1930s than that experience with the airline was.

How so?

In those days, in Gettysburg, South Dakota, you cranked up the phone, and Louise the operator would answer. Suppose your refrigerator wasn’t working – you’d tell Louise it was broken, and she’d give you the name of the guy in town who could fix it. But then she might add that the repairman is usually at the local diner right around now, so she’ll call there first to try to reach him.

Your dad would say we need more Louise in our lives.

Yes – we need to be able to have a real conversation with a digital assistant. An assistant that can reason and think, not just answer a question.

How far in the future is such a conversation?

We’re taking some important steps now, starting with getting humans and artificial intelligence to work together more. Right now, if the digital assistant doesn’t know the answer to a user’s question, it doesn’t do anything, or it just says, “I don’t know.” There needs to be a way for the user to help the assistant learn – essentially create a feedback loop. The more the user can provide input to the assistant, the more the technology can learn and remember.

The relationship between user and assistant grows over time?

That’s the first step, yes. For example, suppose you tell a digital assistant you’d like to get back-row seats to a show tomorrow. Right now, the artificial intelligence probably doesn’t know what “back-row seats” means. So you’d teach it by calling up the theater diagram. This is a master-apprentice relationship, with the human as the master.

What follows that?

Well, there has to be a way to share what the assistant learned from its exchanges with you. So if someone else asks the same question later, there’s a better chance the AI can answer it accurately. Of course, that also raises issues of privacy.

Because the user is sharing what was taught to the assistant?

Yes. It’s a balance between privacy and benefit. In my opinion, there’s no such thing as risk-free technology that gives you everything you want. At the same time, the consumer needs to be in control of privacy. And companies have to make it easier to provide that control so that trust can build up between the user and technology.

Do you see that trust developing?

I think the more we create technologies that augment humans, the more willing people are going be to share the information needed for the assistant to be useful. One way to do that is to build technology that’s extends the human – sort of like the Iron Man’s suit. It makes the human super-human. But the suit can’t do anything by itself.

What is your lab working on now?

My lab at Georgia Tech is called the AI Virtual Assistant (AVA) Lab. We’re aiming to create the next generation of digital assistants, an embodied and fully interactive digital human, Ava. Not a robot – I’m not a roboticist – but I want people to feel comfortable having a conversation with a full-bodied avatar. You could speak to it and make gestures and show expression, and it would understand all of this. And the conversation would be open, not limited to question and answer.

Would this avatar be something we’d see on a screen?

That’s one mode, yes. But virtual and augmented reality would be other ways to interact. For instance, we’d have a meeting in our lab, and all of us would put on augmented reality glasses, and joining us at the table would be Ava, who would be a full participant in the meeting, as an assistant. She could transcribe what’s being said, summarize it, participate in the conversation.

That’s augmented reality?

Yes. The virtual reality version would be similar, although instead of Ava being in our world, we would be in hers.

How far away is such a scenario?

I’d say we will begin to see this type of scenario in just a few years. The component technologies are maturing rapidly in voice and video. The visual graphics technology is pretty good. The conversational AI systems are available in the open domain. One company even has a tool kit for constructing meta-humans. Like I was saying earlier, around 2010, everything was coming together for speech recognition AI. This moment in time feels a lot like that one.

Back in 1987, you built your first speech recognizer while working on your Ph.D. at Georgia Tech. What did that technology look like?

Speech recognition technology saw a large jump in progress in the mid-80s with a technology called Hidden Markov Modeling (HMM). For a class project, I wanted to learn about this new HMM technology. So I built prototype voice-activated calculator. You could ask it to perform calculations, like 37 times 256.

And it would answer.

That’s right. Simple. At the time, speech recognition technology was not good at understanding different people’s voices – it had to be trained for an individual, so it really only worked well for one voice at a time. We had the idea -what if we could have a bunch of recognizers, each trained on the voice of a different person, and then combined them? Then if it heard a voice never before heard, it would match it to the one that sounded closest. We worked on that and wrote a paper. About two years later, that whole area of research called speaker adaptation started getting developed.

How do you currently interact with your own digital assistant?

I use Google Assistant, Alexa and Bixby. Mostly for tasks that are mundane or repetitive, like playing music or finding out the temperature outside. It’s easier to ask a question than to type in “weather forecast next 10 days.” But these are message-in-a-bottle tasks. My frustration from the limits of this experience is actually driving my research to improve it.

You’ve said you came back to Georgia Tech partly for personal reasons (Larry’s wife has family in Tennessee). But what about the professional opportunity made the return to Georgia attractive?

Among universities in the U.S., Georgia Tech has been leading the way with a kind of startup, entrepreneurial culture. CREATE-X (student entrepreneurship program) is a great example. Georgia Tech is also in the middle of artificial intelligence research, which is a national research priority right now. And there’s lots of momentum with the venture capital community here in Georgia, plus Atlanta becoming a hub of AI and tech innovation, with Microsoft and Google expanding here.

Another example of the right things coming together at the same time?

I guess convergence is kind of a theme to this conversation!

This interview represents a compilation and editing of several conversations with Larry Heck.