The young company Brij Medical is rewriting that story. While scars from injury and surgery are inevitable, they can be rendered much less deforming with a little more care – and the Brijjit system of healing.

Supported by Emory, backed by early-stage investment from GRA, Brij Medical is getting traction in cosmetic surgery procedures. Meanwhile, the door is opening to a much wider marketplace.

A lot, it seems.

When wounded skin heals, a complex series of events takes place at the skin’s surface and below. Inflammatory cytokines are released. Cell receptors are activated. Gene expression changes.

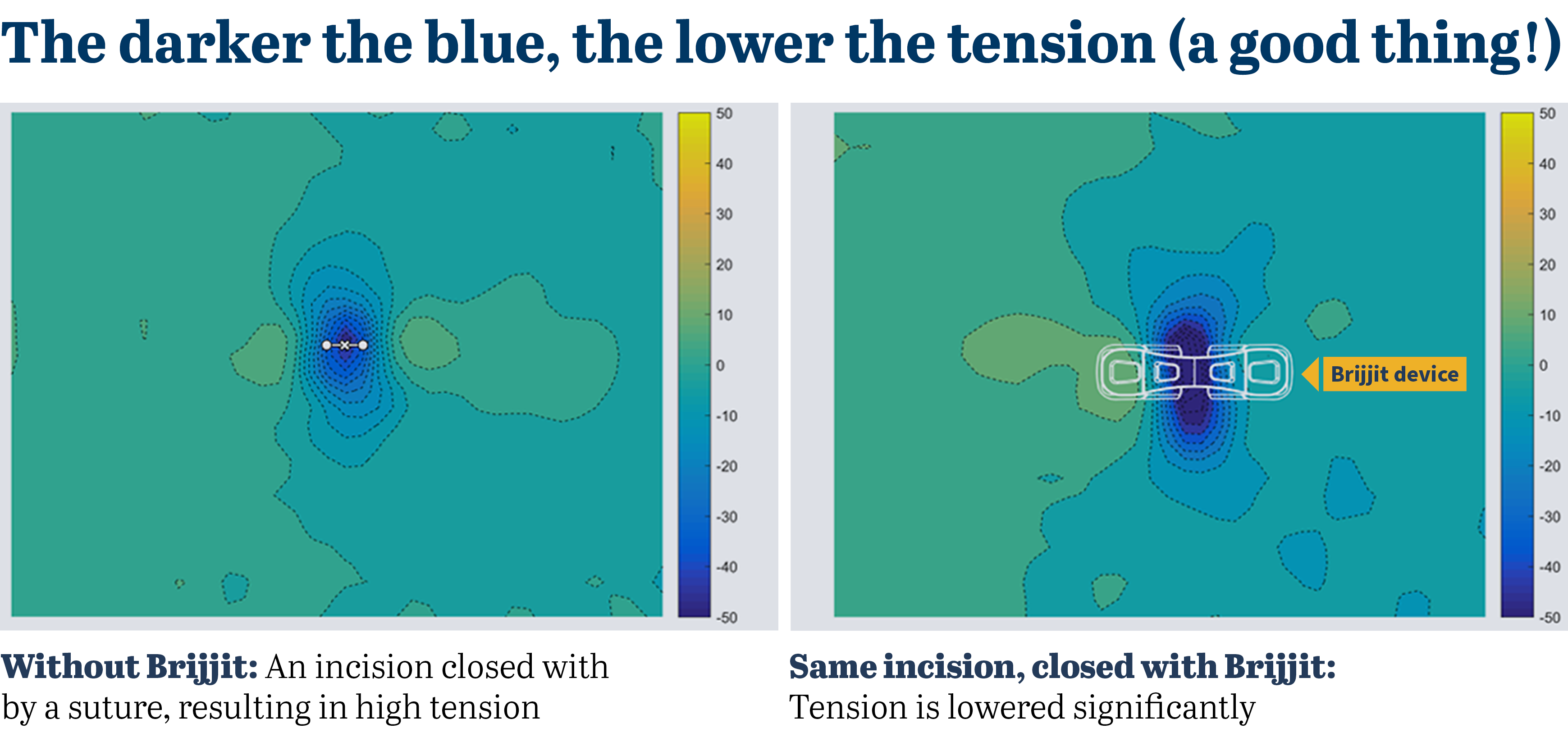

Across this complexity of biology is a key driving factor: Tension.

Simplified, the greater the force pulling apart skin on both sides, the higher the tension. And unmitigated tension begins a chain reaction that results in greater inflammation as well as collagen deposits. The more collagen is released, the worse the scar appears.

Everyday stitches and staples do a good job of closing a wound, but their ability to offload tension is inconsistent, concentrated and temporary. They also introduce foreign bodies into the wound, which causes a tissue reaction.

Suffice to say, a technology that bridges the wound without foreign bodies and lowers tension would bring a better result: a more minimized scar.

The simplicity of the Brijjit device – an elegantly arched 1-inch span of plastic – belies its structural wonder.

Retrieved from a tray, placed on the skin, with a foot pad on each side of the wound, the Brijjit immediately brings closure and control. Medical-grade adhesives keep it that way.

The technical term for this is force modulation, and the Brijjit device is a one-of-a-kind “force-modulating tissue bridge.” It bridges with a bendable backbone of plastic material specially engineered for strength and flexibility.

Yes, but does it work?

“Prior to a full product launch, we kept a very close watch on the first several hundred uses,” says Dr. Felmont “Monte” Eaves, founder and executive chairman of Brij Medical who is also a plastic surgeon. “We wanted to know, did it support the wound for long enough? And were there any reactions that were new to us? How would the patients feel about wearing them? In all cases, the product over-performed.”

A 2021 outside study of 80 patients undergoing breast procedures showed greater than 70% improvement in wound complications when the Brijjit devices were used compared to sutures alone. A review of additional cases is showing improvement of over 90%, and a randomized controlled trial is underway at the University of Texas to evaluate long-term improvement in scar outcomes.

Brij Medical registered its first device with the FDA in 2020. Today, more than 4,000 patients have had wound closures treated with Brijjit, and the number climbs every week.

As the Florida surgeon Dr. Jason Pozner, reports: “I won’t complete a mastopexy now without it.”

The legacy of a poorly healed wound

In the developed world alone, each year between 40 and 70 million people sustain abnormal raised and thick scars following surgery and trauma. Understandably, many suffer from great anxiety and social withdrawal as a result.

The fear of scar is very real: Thousands of patients in the U.S. annually avoid or put off surgery because they simply can’t fathom living with an unsightly scar. More than a quarter-million undergo surgical revisions of scars in the U.S. each year.

“Scars are often seen as just part of surgery, but when you dig a little deeper, you see that the psychological impact they have on patients is very significant,” says Alistair Simpson, Brij Medeical’s CEO.

Adds Dr. Eaves: “I’ve known women who had breast surgery, and for 30 years have not taken off their shirt in front of their husband when they were intimate. That’s how ashamed they were of their scars. It can deeply affect people.”

That’s why Brij Medical got started

While in practice as a plastic surgeon, Monte Eaves was always thinking about wound closure and the aftermath of scarring. So much so, he’d paper-sketch possible alternatives to stitches and staples, looking for new concepts.

He also had conversations with Simpson, who previously had headed global marketing for the wound closure division of Johnson & Johnson. “I’ve known Monte a long time,” Simpson says, “and he’s been thinking about ways to improve things his entire career.”

In 2010, while in private practice in Charlotte, N.C., Eaves had kind of an epiphany. He’d been conceptualizing a wound closure device that went under the skin or sat right on its surface. But one evening, while wearing a Breathe-Right nasal strip to relieve congestion, he hit upon a new idea: Why not bridge above the wound?

“That night, I realized I’d been putting myself in a box,” he says. “When I started thinking about it, I wondered what eliminating part of that box might do.” The concept of Brijjit was born.

In February 2013, Eaves moved his practice and teaching to Emory. Before long, he was talking with Emory’s Office of Technology Transfer about bringing a new kind of wound closure device to market. OTT head Todd Sherer and colleague Kevin Lei encouraged him to enroll in a seven-week course in entrepreneurship held by the Ewing Marion Kauffmann Foundation.

They also introduced him to the venture development team at GRA, who saw the potential of his product. Over the last several years, GRA provided both grants and a Phase 3 loan through its venture program, adding fuel to Brijjit’s movement toward the clinic.

From this point forward

Eaves and Simpson emphasize that Brijjit is not a one-off alternative to closing incisions and wounds. It’s actually a system that promotes better healing.

As with all systems, it works best over time. Surgeons apply Brijjits upon closing; nurses replace them later to keep tension reduced. And because scar formation is a long-term event, patients continue to use different forms of Brijjits during the months of healing that follow. This combination optimizes the system and delivers the best results.

Initial launch has focused on the plastic surgery market, primarily because patients and doctors are highly attuned to minimizing scarring. The thousands of patients who have used the system have provided a trove of valuable market data.

“But there are multiple avenues, channels and specialties where this system can go,” Simpson emphasizes. “We’re looking carefully at our options for a next market. But part of the excitement is it can be used anywhere.”