We’re all familiar with traditional college learning.

You go to class, do your homework, write your papers and take your exams. After a few years, you get a degree.

GRA Eminent Scholar Ed Coyle of Georgia Tech has a larger vision of this learning experience. While at Purdue University in the early 2000s, Coyle came up with a new model: Undergraduates conducting research on real-world problems, across many semesters, while being guided by faculty.

“Imagine giving everyone on campus a chance to work together to do what they really want to do,” Coyle says. “Undergraduates get to do cool projects. They’re mentored by faculty and graduate students, who in turn are advancing their research, with the help of the undergraduates.”

That idea became the Vertically Integrated Projects program, or VIP. GRA helped Georgia Tech recruit Coyle here in 2008, and ever since, the program has flourished at the Institute. Today, 1,760 students comprise an astounding 86 VIP teams on the Georgia Tech campus.

The teams are multi-disciplinary — so you might find, say, accounting and liberal arts students working alongside biology and engineering majors. Newly recruited students learn from fellow students who have served for years (hence, the “vertically integrated” concept). The whole vibe is part academic research, part entrepreneurial startup.

In 2018, Coyle and colleagues began exporting the VIP model to other colleges through the nonprofit VIP Consortium. (GRA VP of Finance Amy Todd served on the board and was instrumental in helping set up the consortium’s financial systems.) Today, the VIP Consortium has more than 40 member institutions from around the world – seven of them in Georgia – with some 6,000 students participating.

GRA invited four University System of Georgia students to share their research experiences with VIP – and how the program is adding relevance to their pursuit of a future career.

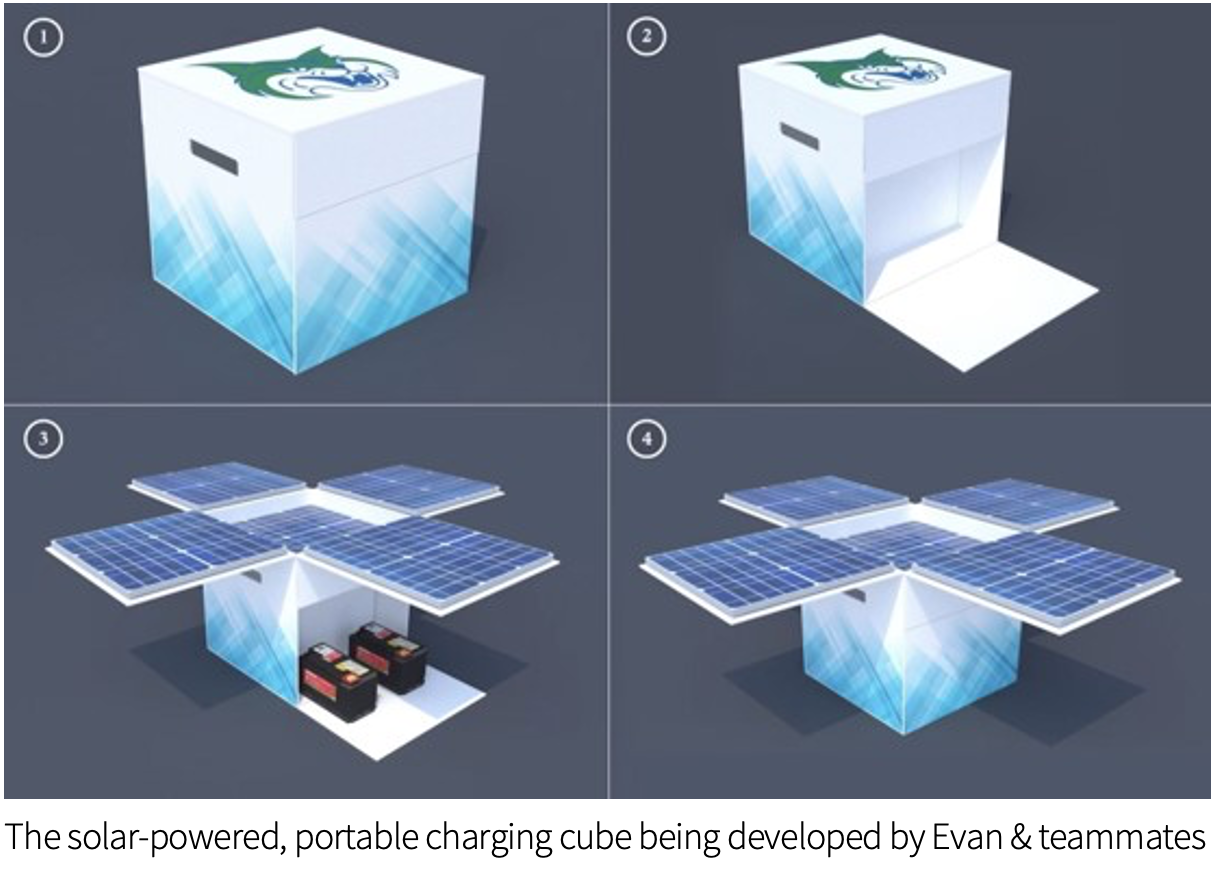

A truck pulls up on a partly cleared street in a tornado-devastated neighborhood. Relief workers hop out, roll up the back door, then unload scores of cubes, each the approximate size of a color laser printer.

The tops of the cubes unfold to reveal solar cells. In a short while, these cells will have collected and stored enough energy to power equipment and recharge devices — providing the stricken with electricity on demand.

This is the vision of Evan Dunnam, part of the GC Solar VIP team at Georgia College in Milledgeville. The team is working with Hasitha Mahabaduge, associate professor of physics, to develop the portable solar generators. Designs have been finalized, and “our next step is to get the materials to build the prototype,” Evan says.

GC Solar has roots in a novel contraption that predates the VIP team. It was an outsized solar-powered charging station called Luma, built by students and wheeled out to points on campus to demonstrate the value of alternative energy. The concept Evan is developing is much smaller, designed to be shipped easily in bulk to disaster zones, while still providing usable power.

“One challenge has been designing the folding solar panels,” Evan says. “First, we worked through a kind of sliding frame, but we ended up using special offset hinges. We had to think about how these could possibly get damaged in shipping, so we added supports to the box to keep them from bouncing on top of each other in a truck.”

“One challenge has been designing the folding solar panels,” Evan says. “First, we worked through a kind of sliding frame, but we ended up using special offset hinges. We had to think about how these could possibly get damaged in shipping, so we added supports to the box to keep them from bouncing on top of each other in a truck.”

While a finished invention is the end goal, the journey there is a research endeavor. It helps that their advisor, Mahabaduge, came to Georgia College from the National Renewable Energy Laboratory, where he set a world record for energy efficiency from solar cells created with the elements cadmium and tellurium.

As part of their research, Evan and another GC Solar team member joined dozens of other students at the state Capital during the 2023 Georgia General Assembly session.

“We shared our poster and explained the [technology] we’re working on,” he says. “Eventually, we want to take the prototype we build to trade shows and gauge the interest of disaster relief organizations.”

A tiny worm has managed to do something extraordinarily big: It developed a way to rid itself of harmful toxins. Strains of this worm, called Caenorhabditis elegans, have achieved such a feat through evolution. Could humans someday replicate this metabolic process to self-purify the body?

Understanding metabolites inside c. elegans will help answer that. Starting fall 2021, Kennady Boyd at the University of Georgia has been contributing to that understanding through a VIP team that had just been formed on campus.

In the early days, Kennady learned to grow the c. elegans worms in the lab. Then she was offered a new role: using high-powered computer software to analyze the structure of the worms’ genes. This knowledge could be used to predict how the genes function, including that mysterious process of the worms’ detoxifying themselves.

“There are three of us on the computational team, all looking separately at data from genetic models,” Kennady explains. “Then we compare what we’ve observed from the data.”

“There are three of us on the computational team, all looking separately at data from genetic models,” Kennady explains. “Then we compare what we’ve observed from the data.”

Graduate students helped Kennady get up to speed on the software. At first, she was coding; by the time she wrapped up her undergraduate education in May 2023, she had helped build a meta-database of all of the genes they’d analyzed.

“It’s like a gene library, and it was a project that had been on everyone’s mind, but it never got started,” Kennady says. “I worked with two other students to create it.”

The VIP experience in the lab of GRA Eminent Scholar Art Edison has set Kennady on a potential career course in precision medicine, a path she really hadn’t considered before VIP. And computational analysis isn’t the only skill she learned through the program.

“The VIP concept taught me how to work together on a team-based project and how to design experiments,” she says. “Also, I sometimes struggle with public speaking in person. But presenting findings from our sub team challenged me, and I’ve gotten more comfortable doing that.”

Gwen Masch may soon be teaching math to middle schoolers. And if all goes to plan, she’s going to have a huge head start.

A senior at Georgia Southern, Gwen is part of a VIP team that’s exploring how to improve the teaching of math. The team is (fittingly) named MATHS, and it focuses on uncovering best practices and promising approaches in math instruction, then sharing them with parents and teachers.

“A lot of parents grew up in a time before hands-on mathematics, so when they look at their child’s math, they don’t always know what it is,” Gwen says. “As a result, helping kids do their math homework can be hard for parents.”

Formed last fall, the MATHS team — the acronym stands for Mentoring Adults as Teachers to Help Students — gives Georgia Southern students a full introduction to academic research. Team members write funding proposals, use grants to conduct studies, then present their findings.

Gwen recalls presenting research with a fellow classmate, Abigail Loren, at the 2022 Georgia Math Conference. Gwen hadn’t yet joined the VIP team, but she had worked as a teaching assistant to Heidi Eisenreich, a Georgia Southern associate professor who mentors the MATHS team.

“Educators from all over Georgia come to the conference — it’s a giant professional development opportunity,” Gwen says. From the experience, she learned more about MATHS and signed up for the VIP program in spring semester. Abigail is on the team, too.

Gwen is now planning workshops to share tools and practices with parents. She’s also studying academic papers and presenting at symposia, and she’s preparing a proposal to present again at the Georgia Math Conference in October 2023.

One area of interest: Math manipulatives, the hands-on classroom activities that help students (and adults) conceptualize math better.

“Manipulatives are imperative in education, but I’ve noticed a lack of them being used in classrooms,” Gwen says. “If our proposal is accepted for the next Georgia Math Conference, I’ll be doing a session on algebra tiles, which are little shapes that represent constant numbers and variables. These really help people understand and remember math concepts.”

Picture two Whirlpool dishwashers, side by side, and you have an idea of the amount of concrete produced each year for every person on Earth.

Concrete is second only to water as the most-consumed commodity in the world. And making the billions of tons of the stuff accounts for nearly 9 percent of yearly global carbon emissions.

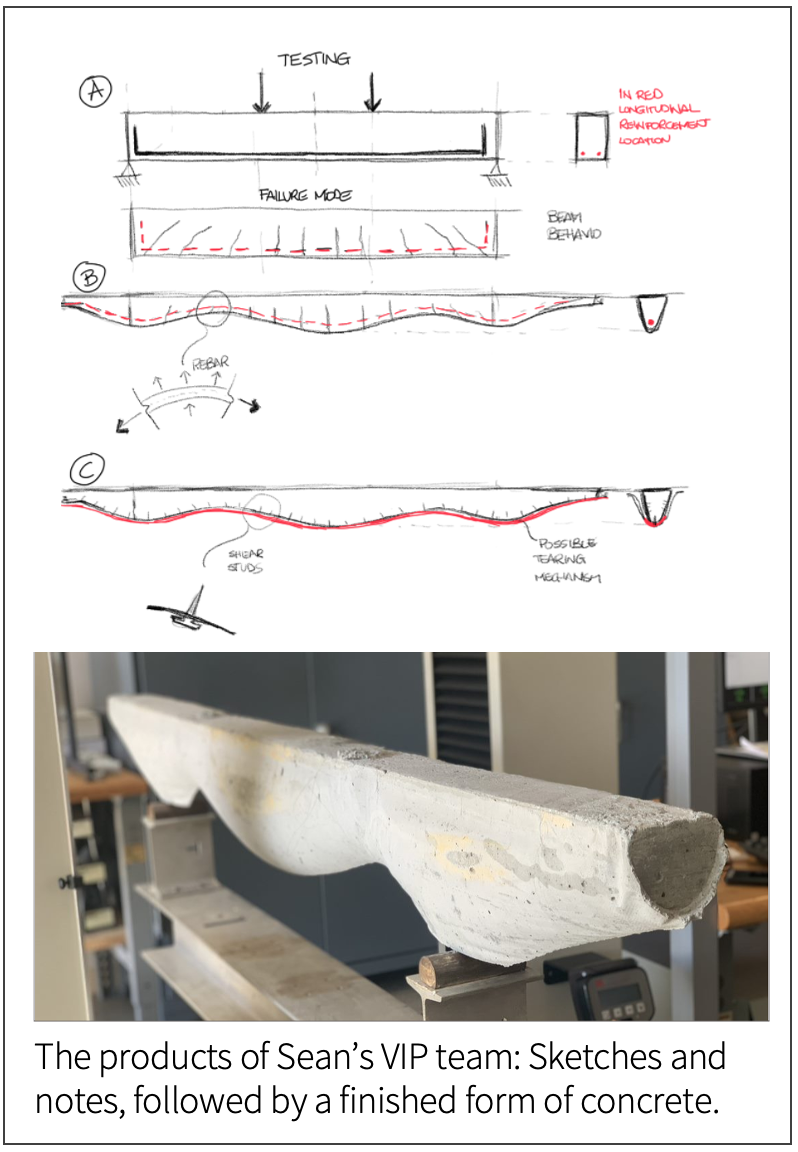

A VIP team of Kennesaw State students is re-thinking the making of concrete for construction. Sean Stadler is one of these students – he and his colleagues in architecture and mechanical and civil engineering work to forge shapes of concrete that are more resilient, cheaper to make and better for the planet.

“Most research on how to optimize concrete focuses on different types of materials,” Sean says, noting that his team does tinker with “cementitious” ingredients in mixes. “But there’s much less research on the shapes that make forms of concretes.”

In focusing on these shapes, Sean’s Re-Forming Concrete team is challenging the convention of simplicity in the design of concrete supports. What if cemented beams weren’t all block towers? Which shapes use less concrete without forfeiting strength? “We’re looking for a new architectural language,” he says.

In focusing on these shapes, Sean’s Re-Forming Concrete team is challenging the convention of simplicity in the design of concrete supports. What if cemented beams weren’t all block towers? Which shapes use less concrete without forfeiting strength? “We’re looking for a new architectural language,” he says.

To develop such a language, the team designs and tests new forms for fashioning concrete supports. Mechanical engineering students design formworks, using computational methods. Architecture students create the forms and cast the beams. And civil engineering students make and test the concrete.

Having pursued these answers for five semesters now, Sean is an example of the longevity of the VIP engagement. “I’m a civil engineering student, but my role has evolved into kind of coordinating all three [disciplines],” he says. His mentor in the effort is Giovanni Loreto, associate professor of architecture and associate dean for research in KSU's College of Architecture and Construction Management; Metin Oguzmert, associate professor of civil engineering, also supports the team.

Sean says the VIP research experience has rounded out his undergraduate education. “The networking I’ve done and the experiences I’ve had speaking at conferences have been invaluable,” he says. “Plus, it looks good on your resume to be doing stuff outside of coursework.”